- Home

- David James Keaton

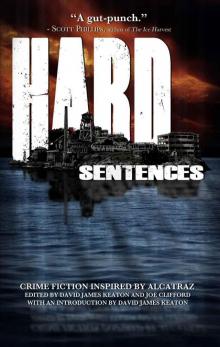

Hard Sentences: Crime Fiction Inspired by Alcatraz Page 8

Hard Sentences: Crime Fiction Inspired by Alcatraz Read online

Page 8

“Okay, dude, looks good, onward and upward.” Bob’s in a hurry like always, gung ho. What Wyatt’s uncles would have called, approvingly, a go-getter. Not the “wander off into the woods or the desert or the mountains” type at all. Focused on a goal like a moth on a pheromone trail, when to be honest most of the rest of the group had been circling the porch light. Wyatt himself hadn’t taken things as seriously as he could’ve, he realizes as he scrambles up the rocky trail, almost seeing Falcon’s tail wagging up ahead. At 27, he was (horribly enough) the grown-up in the room at so many meetings, and he’s always used that to advocate caution, peace, nonviolence. Until Bob came along. He didn’t want to be the guy who got people going nuts and getting killed. But someone got killed anyway, the person—and she was a person, even if she wasn’t a human—who had the least say in it at all. There’s no other reason for anyone to kill her besides the activism, and he’s had threats before, but he honestly didn’t think anyone could have gotten to her so fast and so quietly.

He’d still rather be out on the flotilla next week with the Peace Navy than doing this. The whole thing where he helps map out the action and then stays back at Eddie’s apartment waiting to provide “support,” “logistics,” or whatever fancy word Bob comes up with this time for listening to the news on the radio. It’s just a fig leaf, a childish one, something that’s supposed to make him feel involved but safe. If someone gets killed, or hurt, it’s on him as much as anyone else. He’d always thought that was a line he wouldn’t cross, until he walked out into the back yard Wednesday morning to see why Falcon hadn’t scratched at the door to come back inside. And even now, it’s hard to keep the fury burning in his mind if he remembers it’s not just the faceless bastards who did this thing who could suffer, but Eddie or Beth or, hell, even Bob. Maybe he doesn’t have the passion. Maybe the urge for vengeance just isn’t in him, even though it’s not just a lost, murdered blue merle cattle dog at risk, but every fish and bird that uses the Bay, the ecosystem out beyond, the whales everyone loves, even the tiny crustaceans that no one knows. When you think of what’s at stake, maybe there’s something wrong with him that a murderous urge isn’t burning all the time.

Wyatt’s steps go wrong while he’s thinking this, and he stumbles on a rock. Bob runs into the back of him, banging a bucket inside the curve of his knee hard enough to bring him all the way down. Paint sloshes onto Wyatt’s jeans.

“Dammit!”

It’s sharp, but it’s only a whisper. Wyatt never enjoyed disturbing the quiet dark. Bob backs up a few steps, leaving the cans on the ground and hands high in a placating gesture. The actual words “I’m sorry” aren’t in his vocabulary, but he can manage “Well, shit” and an abashed face for a few seconds. Wyatt, still on the ground, rolls into a sitting position and raises the wrong light to inspect the damage. Instead of blood or, as he hopes, merely dirt on his knee, he sees glowing spatters everywhere. One of these long smears on the ground darts away to shelter beneath an overhang of greywacke.

Wyatt’s mind switches modes instantly, and he scoots towards the vanishing glow, no longer worried about blood. He catches a glimpse of a tail disappearing, and now that his eyes know what they’re seeking, the pattern is instantly recognizable.

A millipede, Xystocheir dissecta dissecta. He’s heard that their cousins on the mainland fluoresce, too, but no one had ever thought to check out these guys. If he hadn’t dropped out of grad school, he could have gotten a hell of a paper out of this.

There are six or eight of the little bastards, all glowing a fine pale-blue, short laceworks of legs fringing their bodies. He has a moment imagining describing all this to Falcon, explaining everything while she cocks her head at such a strange, unearthly light.

“Come on, dude.”

This time Bob does poke him, twice, and Wyatt has no idea how long he’s been staring, and he doesn’t really care. Can’t the man see? He pushes the hand away from his shoulder.

“Man, are you pussing out on me?” Bob’s voice raises uncomfortably over the dull splash of the waves. “What are you doing? Don’t you be pussing out on me now, you asshole. I should’ve known you didn’t have the balls for this.”

Wyatt reaches in and manages to snatch up three scrambling millipedes with one hand. Some old skills never leave. “Look at these.” He tries to shine the blacklight on them, but it’s an awkward angle and they’re still trying to crawl away.

“Okay, we got paint on some bugs,” Bob says. “That’s weird and all but . . . are you high? Did you come out here high? You’re going to fuck everything up.”

Wyatt shakes his head. “This is a genus of millipede found in California and nowhere else in the world. This is exactly the kind of thing we’re fighting for. Take a minute and appreciate them, for Christ’s sake, and let me rest my leg.”

It’s stupid to try to explain anything to Bob, and it’s ruining the moment, but Wyatt is stubborn sometimes. He holds the millipedes out, still expecting to share an epiphany.

This pisses Bob off even more.

“Fine. Stare at bugs. I’m not the guy who found his dog hanging in a tree with its muzzle taped shut and its fucking feet cut off. I’d think you’d care more about that, you gutless wonder.”

Wyatt stares down at his handful of Xystocheir, their antenna wagging gently as they realize there’s nowhere to go. “You know,” he says slowly, trying to sound higher than he’d ever been, “the Indians, when they were here during their occupation of Alcatraz from 1969 to 1971, they used these guys for a ceremony. To prove their bravery before the big confrontations and whatnot.”

Bob will believe any goddamn thing is an old Indian ceremony, Wyatt’s hoping.

“Prove your bravery by goddamn getting up and walking.” Bob says, moving as if to slap the millipedes out of Wyatt’s hand. But Wyatt’s too fast.

“Scared?” Wyatt says, inflecting the word the way his uncles might have, but maybe more stoned. Slower. As though he’s prepared to sit here and be obtuse all night long, staring at the man who knew the painful details of his dog’s death, details Wyatt hadn’t told anyone.

“Scared of what?”

“Eating the millipedes. The Indians did it. It’s not so complicated. It just shows you’re part of the food chain.”

Sorry about this, he thinks to the creatures in his palm, and then he raises his hand to his mouth. It’s an old party trick all magicians and entomologists learn to impress the kiddies, chewing theatrically and dropping one lucky millipede behind him.

He holds out his hand, the two less-fortunate millipedes still caged by his sweaty fingers.

“Your turn.”

Bob stares at him hard, then reaches out and plucks the smallest millipede up, pops it into his mouth, and crunches fast, wincing. Wyatt waits for a retch, but to Bob’s credit he gulps it down fast, then picks up the paint cans with a flourish, as if he’d really just conquered an ancient ceremony of great meaning.

“Okay,” he says, calmer now, “can we go?”

“Sure,” Wyatt says, lurching to his feet, energized. “We’ve only got a bit before it kicks in, so we’d better get as much done as we can.”

“Kicks in?”

“The cyanide. That’s why they glow, you dig? To warn predators they’re loaded full of poison.”

“Jesus Christ!” Both buckets fall with a clatter, long streaks of paint running like insects and soaking into the sandstone all around them.

Bob would have been a shitty Indian, Wyatt thinks with satisfaction.

“Some of them have a dose that will kill a man,” he says. “Others, not quite. That’s where the bravery comes into play.”

Ten seconds’ thought would reveal the holes in that story, but with any luck at all, Bob’s past thinking about anything any time soon.

“You insane bastard,” Bob marvels. “Why would you do that to me?”

“You think we don’t know a rat when we see one?” Wyatt asks him, ashamed that, in fact, they hadn’t.

“You show up from nowhere. You know no one. You have all sorts of money and no job.” He pauses, wonders what other tells they missed early on. “You only ever want to do the glory-hound stuff: arson, guns, fighting with cops. No organizing, no building connections, not even nice, low-key trespassing or civil disobedience. Always the tough-guy bullshit.”

“The hell I am!” Bob’s feeling it already though, slumping downwards along the steep part of the trail, back hunched, not unlike a rat at all.

“You don’t know the first fucking thing about the environment, to be honest. You don’t know the difference between a millipede wearing graffiti and one that glows on its own.”

“You ate one, too!” He’s far below Wyatt on the trail now.

“Yep, too late for me. You got me, like you got Falcon. But if we both die out here, the others will know something went wrong, and they won’t fall into whatever trap you and the pigs had set up for us.”

Bob runs, and Wyatt watches him go. He’ll go for his boat and try to get to medical help across San Francisco Bay, sweating his brains out all the way. And he’ll either make it or be swept out to sea. But he won’t get where he’s going as fast as Wyatt can kayak home. Not with this tide. There’ll be time to warn the others.

There’s a skitter of rocks. A thump and a scream. A splash.

Wyatt thinks, that really wasn’t as bad as I expected.

Then he thinks about how the millipedes with cyanide are the Motiyxia and not the Xystocheir, and the fact that they lived nowhere near the island is a pretty thin fig leaf, even compared to Bob’s plan. He’s killed a man. He finds it hard to care.

He’ll have to leave, since he’d been the last one to see Bob alive, head for the forest or the desert or the mountains that have been spared. He’ll tell the others to go join the flotilla and stop the dumping if they can. The rain and wind would wear away their paint, eventually, and even the unlucky millipede would be replaced by a newly hatched nymph soon enough. He’d find someone to describe the glow to again, someday. Maybe another cattle dog.

The Eighth

by Johnny Shaw

I kept my promise. If I didn’t keep my word, who was I as a wife and a Christian? For all my sins, I would never forget that I held his life in my hands. He loved me and trusted me with what little hope he had left. In a place with no reason for hope, that was everything.

Every eighth of the month for the last six years, I took the journey to see my husband in whatever penitentiary currently housed him. Except when the eighth fell on a weekend, then it was the first Monday after.

As Harold moved across the country, I moved with him. Once I picked up and moved from my hometown, it wasn’t anything to do. I wasn’t leaving anything, my roots already severed. I became accustomed to starting in a new town, a new home, and a new life. Eight moves total. Indiana, Illinois, Kansas, and for the last sixteen months, San Francisco. The final stop, one which we spent both together and apart.

Our journey together would end here.

My monthly ritual on visiting days was not unpleasant. I considered myself a happy person, but on those days I had given up trying to control my feelings. I usually settled on somber as a more appropriate mood. Not glum, but stoic. Inside, I could find peace in the repetition, if not joy. During the rest of the month, my routine made it easy to forget that my husband was only two miles away. But on the eighth, I received the perennial reminder of the strangeness of that reality.

One visit per month by permission of the warden. That was all that was allowed. What harm would it have done for me to see him more than that? Twice, even? Was it a part of his punishment, or were they worried we would plan an escape, if we only had more time? Or was it just laziness? Fewer visits meant less work. I’d been in enough prisons to know that the rules were rarely developed with the prisoners in mind. Feckless administrators with uncreative solutions to problems that didn’t exist.

I left my small house at first light and walked through the low mist that filled the streets. I never ate breakfast, settling for the luxury of two cigarettes on the short walk. I found different routes, but always ended up in the same place. The coldest place in the city. The pier. With the wind from the bay cutting through my coat, I waited with a small group of men. Some of the faces were familiar, others new to me. Three men in uniforms, two men in dark suits, and another man carrying a black medical bag. Guards, lawyers, and a doctor or dentist. Men commuting to work. I was the only one boarding to visit a prisoner.

The ferry pointlessly arrived on time. I suppose I should admire the ferryman’s punctuality, but never had anybody been in less of a hurry than the people going to or from Alcatraz Island.

Women and children disembarked from the small boat. The wives and children of the guards who lived on Alcatraz heading into the city to do their weekly shopping or to attend school. They gave me knowing looks, eyes full of pity or spite.

I boarded with the men, nodding to the ferryman. He knew me by sight, nodded back. We hadn’t exchanged a word to each other in at least half a year. What was there to say?

I found a seat. The other passengers and I rode in silence as the ferry chopped through the Bay toward Alcatraz. The trip never took more than fifteen minutes, but every second held a moment. I no longer looked back at the city. Even our most recent past is our past. I kept my eyes on the rocky island as it approached. That was my present and future.

By the time we reached the opposite pier, my cheeks were wet with tears. The men on the boat looked away, assuming that I was crying, not that I was sensitive to the diesel fumes and salt water. I had finished doing all my crying a long time ago. Dabbing at the corner of my eyes with my handkerchief, I did my best to avoid smearing my makeup. I wanted to look my best for Harold.

I stepped off the boat. No hand from the ferryman or the guards that waited on the dock. They consulted their paperwork, grunted commands, and pointed me where I already knew to go. They never once looked me in the eyes. I never took it as insult, but instinct. These were men who were paid to oversee the imprisoned. If they were like me, they had been taught in church to treat all men the same. Here they had been taught to treat these men differently. That forced them to treat everyone different.

Nobody was born a prison guard. They had to learn how to perform their role. As I had learned to be a prison widow. Nobody taught me how to be married to a man serving a 99-year sentence.

Through the repetition of processing my visitation, I was treated like a stranger. Faces I saw monthly asked the same questions. I filled out the same forms, identically except for the year. With two guards to accompany me, we walked through one building, outside to another, and down a long hallway into the visiting room.

Save for the guard that monitored the visit, I was alone in the spare room. Four windows of thick glass, each with an intercommunication device that I would use to interact with my husband. No chance of physical contact. The salt air had rusted the exposed corners of the chipped counter. Some of the pea green paint peeled to reveal gray.

I waited for Harold, sitting on the backless stool. I glanced at the guard who would listen to every word that we spoke to each other. Another rule. So many rules. Harold wasn’t even allowed to talk about his life in the prison. Which gave him very little to talk about it.

It meant that I did most of the talking.

Harold gave me the smile that had made me fall in love with him. Like he was thinking of a joke, but it was only for him. He looked at me like a husband should. He made me feel beautiful, desired, and loved, even in the dank surroundings.

Harold seemed to have aged another year in the month that I’d seen him. A few more lines, thicker bags under his eyes, his hair thinning in the middle.

“You look well,” I said.

“Not as good as you, baby. You’re beautiful as ever.”

“The California air suits me.”

“I told you I’d take you to see the West Coast.”

I laughed, not the fir

st time he’d told that joke.

“You don’t miss home.”

“This is home now.”

“Not too cold for you?” he asked

“No snow. I don’t miss the snow.”

“But it’s colder here, you know? Illinois, Indiana, Kansas, even Minnesota, those were places where the cold made sense. Here, I don’t know. Maybe it’s just here inside, but some days I feel like I can’t ever get warm. Like I ain’t never going to be warm again.”

“I might be able to buy a coat for you. I can write a request to Warden Swope.”

“Save your money. I have a good coat. Good enough. I just feel like complaining.” Harold tried to smile again, but he couldn’t hear the joke. “The cold is just colder.”

“Are you sleeping? You look tired.”

“Better. What else is there to do?”

“Are you reading your Bible?”

“Every night, baby.”

We told each other what we wanted to hear, an unspoken agreement. Lies and truth didn’t matter. The words didn’t matter. We were never going to be in the same room together. I would never touch the man I married again. Why fight? Why bring conflict to the brief purgatory we had? Our marriage was already separated by steel and concrete and men in uniforms and the entire San Francisco Bay.

The silences were the hardest. There were always silences. It felt like a personal failure to let even the most mundane conversation ebb. As much as I prepared myself to have things to talk about, I got lost in the discomfort of it all. I limited myself to certain topics. I didn’t want to talk about things that he would never have again. He would never walk in a park, eat an ice cream cone, or travel farther than three hundred yards from where he sat.

Hard Sentences: Crime Fiction Inspired by Alcatraz

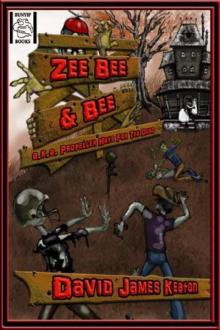

Hard Sentences: Crime Fiction Inspired by Alcatraz Zee Bee & Bee

Zee Bee & Bee The Last Projector

The Last Projector